|

Cathay Williams, Female Buffalo SoldierServed 1866-1868 |

|

|

|

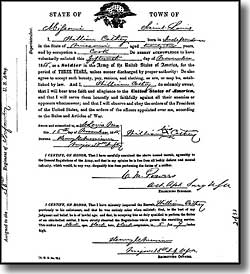

On November 15, 1866, Cathay Williams enlisted with the United States Regular Army in St. Louis, Missouri, for a three year tour of duty. She told the recruiting officer that she was 22 years old and a cook. She said her name was William Cathay and she was born in Independence, Missouri. She was illiterate and didn't know that her papers read "William Cathey" when she gave them to the recruiting officer. The records from the recruiting officer state that William Cathey was 5'9", black eyes, black hair, and black complexion. An army surgeon examined her upon enlistment, and determined that the recruit was fit for duty. The exam had to be cursory, just checking for obvious and superficial impairments or abnormalities. If either the surgeon or the recruiting officer realized that William Cathey was female, well... 19th century U.S. Army regulations forbade the regular enlistment or commissioning of women. Other than her birthplace, we know nothing of this woman prior to her enlistment in the U.S. Army. Even her age is uncertain. She might have been only 16 years old and, as do so many boys who lie about their age, she may have, too. The 1860's US Army hardly ever checked age claims, nor did they ask for proof of identity. As to why she might enlist in the Army, as a black woman in 1866 her prospects were pretty sad. But the army paid her more as a black male cook than she could have ever earned as a black female cook. |

|

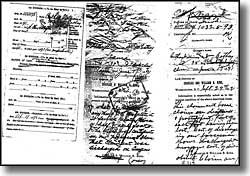

As women disguised as men had fought in the volunteer armies of the Revolution and of the Civil War, Cathay Williams may be the first to have served in the United States Regular Army in the 19th century. She is also the only documented African-American woman who served in the U.S. Army prior to the official introduction of women in 1948. Upon enlistment, as William Cathey, she was assigned to the 38th U.S. Infantry, which had been officially established in August, 1866, as a designated, segregated African-American unit. (The 39th, 40th, and 41st Infantries were the other designated and segregated black units created that year.) The segregated African-American regiments were commanded by white officers, with the regimental headquarters of the 38th at Jefferson Barracks, Missouri. On February 13, 1867, Company A of the 38th Infantry was officially organized, and William Cathey, along with 75 other black privates, was mustered into that company at Jefferson Barracks. However, at that time, she was in an unnamed St. Louis hospital, suffering an undocumented illness. By April, 1867, William Cathey and Company A had marched to Fort Riley, Kansas. On the 10th of April, she went to the post hospital complaining of "itch". ("Itch" was usually scabies, eczema, lice, or a combination thereof, part the filth of camp life.) On April 30, along with 15 other privates, she was recorded as being ill in quarters. Because they were sick, all 16 privates had their pay docked 10 dollars per month for three months. She returned to duty on May 14, indicating that something other than "itch" had bothered her. In June, 1867, the company was at Fort Harker, Kansas. On July 20, 1867, they arrived at Fort Union, New Mexico, after marching 536 miles. On September 7, Company A began the march to Fort Cummings, New Mexico, arriving October 1. They were stationed there for eight months. From the records, it looks like she could march long distances as well as any man in her unit. When not on the march, all privates did garrison duty, drilled and trained, and went scouting for signs of hostile Native Americans. William Cathey participated in her share of their duties. There is no record that she ever engaged an enemy or saw any form of direct combat while she was enlisted. On January 27, 1868, she was admitted to the post hospital at Fort Cummings, citing rheumatism. She returned to duty three days later. On March 20, she was again admitted to that hospital with the same complaint. Again, she returned to duty within three days. On June 6, the company marched for Fort Bayard, New Mexico, completing the 47 mile march on the 7th. This was her last posting during her army stint. On July 13, she was admitted into the hospital at Fort Bayard, and this time was diagnosed with neuralgia (a catch-all term for any acute, intermittent pain caused by a nerve, or some part of the nervous system - which could actually be any number of symptoms from a wide range of diseases). She was gone from duty for a month. This was her last recorded medical treatment while in the Army. During her entire military career, William Cathey was recorded as being in four different hospitals on five separate occasions, for varying amounts of time. And no one discovered that William Cathey was really Cathay Williams, am African-American woman. The fact that in five hospital visits, no one realized the sex of William Cathey raises a few questions about the quality of medical care available to the soldiers of the U.S. Army, even by 19th centuty standards, or at least to the African-American soldiers of that time. Obviously, she was never fully undressed during her hospital stays. There is no record of what kind of treatment was given to her at any of the hospitals. But whatever treatments she did receive, they obviously did not work. |

|

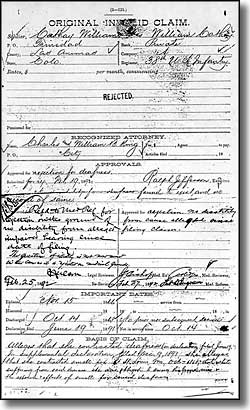

On October 14, 1868, William Cathey and two other privates in Company A were discharged at Fort Bayard on a surgeon's certificate of disability. William Cathey's certificate included statements from the captain of her company and the post's assistant surgeon. The captain stated that Cathey had been under his command since May 20, 1867 "... and has been since feeble both physically and mentally, and much of the time quite unfit for duty. The origin of his infirmities is unknown to me." The surgeon stated that Cathey was of "...a feeble habit. He is continually on sick report without benefit. He is unable to do military duty.... This condition dates prior to enlistment." Despite the three-year enlistment, she served her country for just under two years. After her discharge, she resumed wearing women's clothing and went back to being Cathay Williams. She worked as a cook for the family of a colonel in 1869 and 1870 at Fort Union. Then she went to Pueblo, Colorado and worked as a laundress for a Mr. Dunbar. In 1872, she settled permanently in Trinidad, Colorado, making her living as a laundress and part-time nurse. In late 1889 or early 1890, she was hospitalized in Trinidad for nearly a year and a half but there's no record detailing the nature of her illness. She was indigent when she left the hospital, so in June 1891, based on her military service, she filed for an invalid pension. Her application brought out the fact that an African-American woman had served in the Regular Army. Her original application, sworn before the local County Clerk, gave her age as 41. She stated that she was one and the same person as William Cathey who had served as a private in Company A, 38th U.S. Infantry, for just under two full years. In her application she claimed that she was suffering deafness, rheumatism and neuralgia, all of which she had contracted while in the army. She felt herself eligibile for the invalid pension because she could no longer sustain herself through manual labor. The clerk recorded her attorneys as Charles and William King of Washington, D.C., most likely "professional pension claim handlers" (the kind of creatures most of us know as "shysters"). She filed a supplemental declaration the following month in Trinidad. In the supplemental declaration, she contended that she contracted smallpox at St. Louis in October, 1868, and that she was still recovering from that disease when the Army had her swim across the Rio Grande River on the way to New Mexico. She stated that the combined effects of smallpox and exposure were what led to her deafness. Her attorneys never noticed the discrepancies of dates in the July, 1891, declaration (she swam across the Rio Grande during the march from Fort Harker to Fort Union in the summer of 1867, among other discrepancies). |

|

On September 9, 1891, a medical doctor employed by the Pension Bureau examined Cathay Williams in Trinidad. His job was to provide a thorough examination of the patient and a complete description to the Pension Bureau of her physical condition at the time of the exam. The doctor described her that day as 5'7', 160 pounds, large, stout, and 49 years old. He said she wasn't deaf because she could hear a conversation. He also reported no physical changes in her joints, muscles, or tendons that might indicate rheumatism or neuralgia (obviously he didn't know that neuralgia was a problem of the nerves, not the muscles, making us question his competency). The doctor also reported that, on both feet, all her toes had been amputated and she could only walk with the aid of a crutch. His records provide no explanation as to how, why or when this happened. Other than the loss of her toes, the doctor stated she was in good general health. He did declare the impairment caused by the amputations permanent but his opinion as to a disability rating was "nil". In addition to ordering her physical examination, the clerks at the Pension Bureau in charge of her case solicited information from her private doctors. Those men could not, or did not, give up any information. While it is apparent the amputations happened after her military service, those severed toes are still another unexplained incident in the life of Cathay Williams. |

|

In February, 1892, the Pension Bureau rejected her claim for an invalid pension and notified her lawyers in April. They didn't respond until the following September. While they conceded there was no proof she acquired deafness in the line of duty, they tried to follow up on the disability of the feet and claimed she lost her toes due to 'frosted feet'. Frostbite would have qualified her for an invalid pension, if she has suffered it during her service, and if it had been recorded as happening. The Pension Bureau rejected her claim on medical grounds, stating that no disability existed. In those days, there were five lawful grounds for denial of an invalid pension:

Perhaps the Trinidad doctor's report, which basically stated she was fine, held the most weight in the case. But Cathay Williams was disabled. She could only walk with the permanent aid of a crutch. And, for different reasons, the army itself had deemed her disabled for service in 1868. The pension clerks offered no explanation for picking the "no disability" grounds for denial of the pension. The review personnel of the Pension Bureau rubber-stamped the decision, and didn't raise any questions about the case. The fact that the Pension Bureau chose the least defensible reason for denial, that she was not disabled, brings up the question of how fairly and how thoroughly her case was treated. She was truly disabled. She may not have been an invalid in the strictest sense of the word, but as a laundress, her ability to work and make a living was severely limited by her not being able to walk or stand without aid. Surprisingly, the Pension Bureau never questioned her identity, and never appeared to doubt that William Cathey of the 38th Infantry and Cathay Williams of Trinidad, Colorado, were one and the same. By 1891, the Pension Bureau had already dealt with more than one woman who had disguised herself as a man and served her country during the Civil War and had come back to apply for some sort of pension. And women who applied for pensions based upon army service usually met with resistance, not just from the pension clerks, but from the army itself. Maybe a small, brief notation in Cathay Williams' pension file sums it up. In the margins, a clerk wrote that the question of identity was never raised as the claim was rejected for medical reasons. This one sentence opens the possibility that her service may have been questioned had there been no way to deny her claim on strictly medical grounds. As we have almost no records of Cathay Williams before her military enlistment, we also have almost no records of her after her pension application was denied. She must have died somewhere between 1892 and 1900 as her name doesn't appear on the Census rolls for Trinidad from 1900. She was an improbable pioneer. Her army service was short-lived and not brilliant. She was mustered out of the army through no fault of her own - she was just "unhealthy." She was uneducated, she possibly suffered from a long-term debilitating disease (mild diabetes - which would account for the amputated toes), in lowly circumstance, and perhaps even somewhat unintelligent. What we do know about her suggests that her life was difficult. The importance of Cathay Williams' life isn't only in the recognition that she is the only documented black woman who served in the Regular Army infantry during the 19th century but that she did so against incredible odds. And she most probably wasn't trying to prove anything to anyone, she was just trying to make a living and get by in a very hard time.

For more about Buffalo Soldiers

|

|

|

|

| Index - Arizona - Colorado - Idaho - Montana - Nevada - New Mexico - Utah - Wyoming National Forests - National Parks - Scenic Byways - Ski & Snowboard Areas - BLM Sites Wilderness Areas - National Wildlife Refuges - National Trails - Rural Life Sponsor Sangres.com - About Sangres.com - Privacy Policy - Accessibility |

| Documents are courtesy of the National Archives Text Copyright © by Sangres.com. All rights reserved. |