|

Trail of Tears National Historic Trail |

|

|

The Trail of Tears Memorial at the New Echota Historic Site in Georgia |

|

"It is with considerable diffidence that I attempt to address the American people, knowing and feeling sensibly my incompetency; and believing that your highly and well improved minds would not be well entertained by the address of a Choctaw. But having determined to emigrate west of the Mississippi river this fall, I have thought proper in bidding you farewell to make a few remarks expressive of my views, and the feelings that actuate me on the subject of our removal ... We as Choctaws rather chose to suffer and be free, than live under the degrading influence of laws, which our voice could not be heard in their formation." "In the whole scene there was an air of ruin and destruction, something which betrayed a final and irrevocable adieu; one couldn't watch without feeling one's heart wrung. The Indians were tranquil, but sombre and taciturn. There was one who could speak English and of whom I asked why the Chactas were leaving their country. "To be free," he answered, could never get any other reason out of him. We ... watch the expulsion ... of one of the most celebrated and ancient American peoples." |

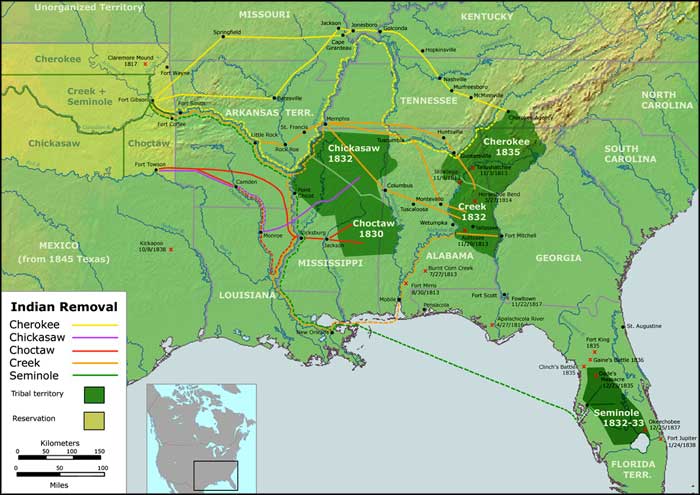

For the most part, the Trail of Tears resulted from the forced Native American removals from the southeastern states between 1831 and 1839. The mostly forcible emigration of tens of thousands of Native Americans who had previously been living as autonomous nations within the United States was facilitated by the Indian Removal Act of 1830, championed by President Andrew Jackson. The primary target of the Indian Removal Act was the Five Civilized Tribes: the Choctaw, Chickasaw, Seminole, Muscogee-Creek and Cherokee Tribes. All of them were forced off land they had inhabited for hundreds of years and moved to what was then Indian Territory (Oklahoma). Some members of the different tribes were allowed to remain in their homelands, but these folks were also required to submit to white laws and white justice. Between 1831 and 1837, some 46,000 Native Americans from the southeastern states had been removed and some 25 million acres of land were opened for settlement by whites. |

George W. Harkins, Choctaw chief The Choctaw were the first tribe to agree to be moved. They had been living mostly in the area of what is now Alabama and Mississippi but in their dealings with the European/American invaders, they had seen the writing on the wall and made an agreement to go voluntarily. They were gathered into two main groups, one at Memphis, the other at Vicksburg. The plan was to start moving on November 1, 1831. A horrible winter moved in early that year and no one was prepared for it. The Memphis group started out in wagons but the roads and rivers flooded. So they were moved onto steamboats that were supposed to take them up the Arkansas to their new homes in Indian Territory. They made it 60 miles, to Arkansas Post. Then the temperature dropped and the river clogged with ice. For weeks the tribespeople got one turnip, a handful of boiled corn and two cups of heated water per day. Finally, the government sent 40 wagons from Little Rock to transport them to Little Rock. Once in Little Rock, a news reporter is said to have quoted one of the Choctaw chiefs as saying this was a "trail of tears and death." As bad as the Memphis group had it, the Vicksburg group started out about the same time, led by an incompetent American guide: they were lost in the New Providence swamps for months. Almost 17,000 Choctaws began the move to Indian Territory. There's no official count but between 2,500 and 6,000 of them died en route. Between 5,000 and 6,000 Choctaws stayed behind in Mississippi, subject to harassment, intimidation and years of legal conflict. Their properties were burned, their fences and crops destroyed, many of them spent years in jail on various trumped up charges. In most respects, they were better educated and more civilized than the white folks who replaced them. |

Selocta, a prominent Muscogee-Creek chief The Creeks had a different problem to face: the personal involvement of President Andrew Jackson. In those days he was commanding officer of the US military in the southern states. During the War of 1812, many Creeks were driven to ally themselves with the British because of years of white American encroachments on their lands. In March, 1814, Jackson fought the Red Sticks Creeks at Horseshoe Bend in Alabama, and his men killed more Native Americans that day than in any other battle ever fought against Native Americans. The Treaty of Fort Jackson, signed on August 9, 1814, ended the Creek War with the Creeks ceding 23 million acres of land in Georgia and Alabama. With that, the Creeks were restricted to a smaller piece of land mostly within the boundaries of Georgia. The Treaty of Ghent was signed in December, 1814, officially ending the War of 1812. Article IX of that treaty restored the sovereignty of Indian nations and their rights to their lands. The American government never honored that. In 1825, the Governor of Georgia negotiated the Treaty of Indian Springs with his cousin, a Creek chief. That treaty ceded the remaining Creek lands in Georgia to the State of Georgia. The Creek National Council protested all the way to Washington and succeeded in getting the Indian Springs treaty nullified by the President and a new, more generous treaty ratified by Congress. However, Georgia Governor Troup ignored the new agreements and ordered the Georgia Militia to begin forcibly removing the Creeks and shipping them west to new lands along the Arkansas River in Indian Territory. President John Quincy Adams moved to intervene with federal troops but when Troup mobilized more militia, Adams backed down saying "The Indians are not worth going to war over." With that, nearly all the Creeks living in Georgia headed west. The 20,000 Creeks still living in a narrow strip of east Alabama in those days found the Alabama government forcing white laws on them and abolishing their tribal governments. After many encroachments by white squatters, shooting started. That led to the Treaty of Cusseta, signed in 1832 and ceding all Creek lands east of the Mississippi to the federal government in return for stipulated land claims in the former Creek territory. Most tribe members didn't have a clue as to what was going on and many of them were swindled out of their property by incoming whites. Those who held onto their land and weren't swindled were overrun by white squatters, and the shooting started again. Andrew Jackson was President in those days and his response was to send out the Army to collect the Creeks and forcibly transport them to Indian Territory. |

Map of the Trails of Tears, click on the map for a larger version |

|

|

|

| Index - Arizona - Colorado - Idaho - Montana - Nevada - New Mexico - Utah - Wyoming National Forests - National Parks - Scenic Byways - Ski & Snowboard Areas - BLM Sites Wilderness Areas - National Wildlife Refuges - National Trails - Rural Life Advertise With Us - About This Site - Privacy Policy |

| Photos are courtesy of the National Park Service or are otherwise in the public domain. Map of the Trails of Tears courtesy of Nikater. Text Copyright © by Sangres.com. All rights reserved. |